By Jericho Jake Slade

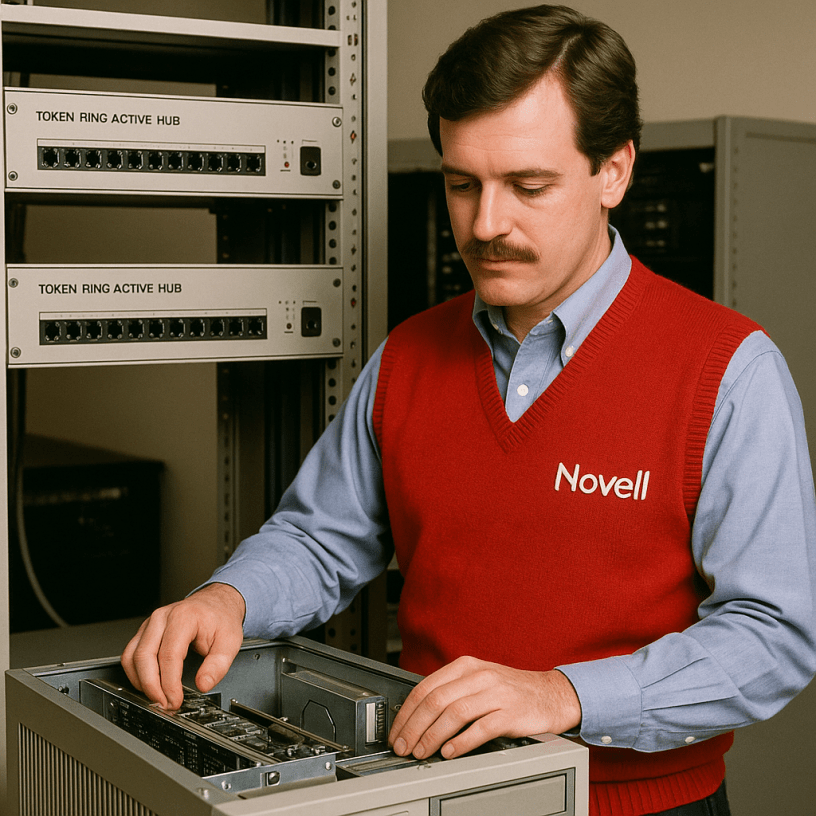

In the mid-to-late 1990s, when corporate networking was still wrapped in superstition and vendor gospel, there was a Novell technician in Chicago who could do something management talked about as if it required a secret handshake and a security clearance. He could configure a Novell server to act as both a file server and a bridge between a Token Ring network and an Ethernet network.

This impressed exactly the kind of people who didn’t understand what it involved.

At the time, Token Ring still enjoyed a reputation for being “more secure” than Ethernet. The reasoning, repeated solemnly in conference rooms, was that Token Ring didn’t suffer from collisions the way early Ethernet did. Never mind that no one at the desktop level could tell the difference. Never mind that collisions were a solvable engineering problem rather than a moral failing. Someone at IBM sold that story well, and corporate America bought it gladly.

Ethernet, meanwhile, was cheaper, faster, and obviously going to win. That made it suspect. Executives tend to distrust things that work better and cost less. Bridging the two networks sounded risky, complex, and important — all the right qualities for something management could admire without touching.

The reality was less dramatic.

The Novell tech installed one Token Ring card and one Ethernet card. He bound them correctly to NetWare. Once the operating system recognized both cards, it handled the bridging automatically. There was no act of genius. No architectural breakthrough. The system did what it had already been designed to do, provided someone didn’t get clever and interfere.

The miracle, such as it was, consisted entirely of restraint.

That restraint, unfortunately, is invisible to management.

From their perspective, the skill had value because it sounded exotic. From the inside, it was situational knowledge — precise, practical, and guaranteed to expire. Ask the Novell tech to do it today and he couldn’t, nor should anyone expect him to. Novell is gone. Token Ring is extinct. Ethernet didn’t just win — it absorbed the competition’s supposed advantages and moved on.

Switched Ethernet quietly solved the collision problem that once justified entire procurement strategies. No speeches were given. No executives apologized. The mythology simply evaporated.

That’s how technology actually evolves. Quietly. Incrementally. Without asking permission.

Management, however, prefers a different story.

They like to believe expertise is permanent and embodied in special people with impressive titles. They are deeply uncomfortable with the idea that many systems are self-solving once properly configured — and that the most valuable technical skill is knowing when to stop touching things. Quiet competence doesn’t look good in a quarterly review.

So the Novell tech became “the guy who could do that thing,” which is corporate shorthand for useful, underpaid, and not going anywhere. His work produced no spectacle. The network didn’t crash. No alarms went off. Nothing happened — which is precisely what infrastructure is supposed to do.

Naturally, this was not rewarded.

Non-technical management has always struggled to value work that happens behind the curtain. If it can’t be turned into a presentation, a metric, or a personal brand, it might as well not exist. Flash gets promoted. Confidence gets bonuses. The people who quietly keep systems running are treated as interchangeable until the day they’re gone.

And they were never paid what they were worth.

Instead of rewarding understanding, organizations mythologize complexity. They talk about systems as if they were unknowable beasts, when in reality they are collections of rules, interfaces, and assumptions. That mythology serves a purpose. It protects hierarchy. It excuses bad decisions. It ensures that failure can always be blamed on “technical issues” rather than managerial ignorance.

The Novell tech never bought into that story. He understood that the operating system already knew how to bridge the networks. His job was to align the pieces and get out of the way. That kind of clarity is dangerous in organizations built on confidence theater.

So it was never truly valued.

This wasn’t unique to networking. The same pattern plays out anywhere complex systems exist — finance, healthcare, government, media. The people who understand how things actually work are sidelined because their understanding exposes how unnecessary much of the surrounding ceremony really is.

The gap between how systems are described and how they operate is where real leverage lives. It’s also where institutional failure quietly accumulates. When organizations reward storytelling over comprehension, they end up managing illusions instead of mechanisms — and acting surprised when reality stops cooperating.

The Novell tech didn’t set out to make a statement. He just did the job correctly, got paid less than the value he produced, and watched management misunderstand it in all the usual ways. Years later, the hardware is gone, the protocols are obsolete, and the skill itself is worthless.

The lesson isn’t.

Systems don’t fail because they’re too complicated to understand. They fail because the people who understand them plainly are ignored — while the people who were sold the story stay in charge.