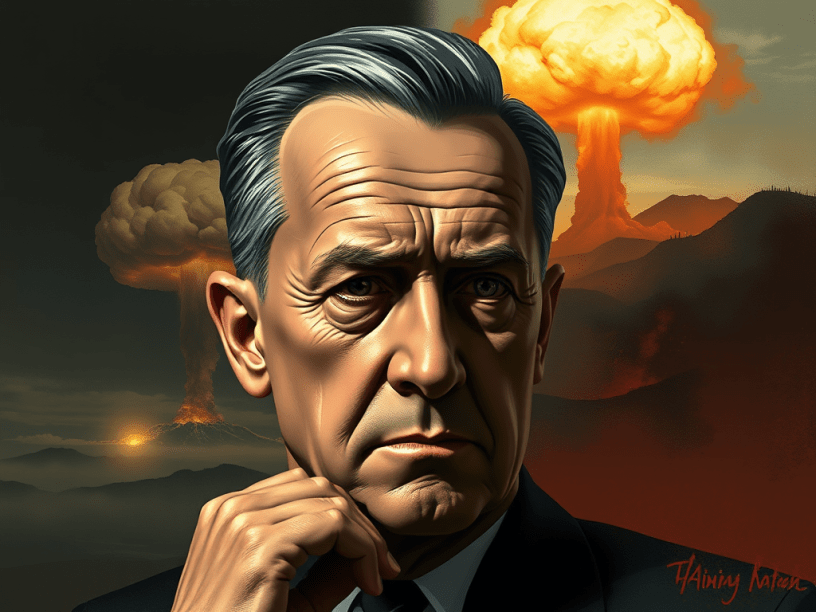

Harry S. Truman. The man who sat behind the biggest button in human history and didn’t hesitate to push it — twice. In August 1945, he dropped two atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, ending World War II in a way no one could have imagined. The world watched in horror and awe as mushroom clouds symbolized not just American might, but Truman’s steely resolve.

But here’s the twist in the Truman saga: after that bold, world-altering decision, the man who once unleashed hellfire from the skies suddenly became a hesitant, cautious, second-guessing politician. You’d think a guy who ended the deadliest war in history with two nuclear punches might carry that same confidence into his next crisis. You’d be wrong.

Enter Korea, 1950.

When North Korea stormed across the 38th parallel, Truman had the perfect chance to prove he could be decisive without radioactive fallout. Instead, he waffled. He half-fought the war. He underfunded it. He underestimated the threat. And worst of all, when his best military mind — General Douglas MacArthur, the war hero of the Pacific, the liberator of the Philippines, the man who knew how to win — pushed for bold action, Truman fired him.

Fired him.

Let’s not get too sentimental about MacArthur. He was a prima donna with a God complex and a flair for drama. But he also had a strategy. He wanted to win. Truman? He wanted not to lose — or worse, he wanted not to provoke. It’s as if seeing the aftermath of Hiroshima and Nagasaki spooked him so badly that he vowed never to make a bold move again. That’s not leadership — that’s PTSD in a suit.

When MacArthur proposed bombing Chinese supply lines in Manchuria to stop the waves of Chinese troops pouring into Korea, Truman said no. When MacArthur asked for more troops and air support, Truman dragged his feet. The man who once said, “The buck stops here,” suddenly started passing it faster than a hot potato at a church picnic.

And then, in April 1951, with public support behind MacArthur, Truman pulled the trigger — not on China, not on North Korea, but on MacArthur himself. He relieved him of command for insubordination, but what he really did was decapitate his own war effort and signal to the world that America had no stomach for victory. It was a warning shot, but aimed at the wrong man.

The result? A three-year meat grinder of a war that ended right where it began — with Korea divided and tens of thousands dead for what amounted to a bloody, expensive tie. All because Truman got gun-shy after Hiroshima.

This isn’t just about one war. It’s about a president who lost his nerve at the worst possible time. The consequences of that timidity rippled through history — a divided Korea, a belligerent China, a Vietnam War that learned all the wrong lessons from Truman’s half-measures. And don’t forget: we still have troops in South Korea 70 years later, cleaning up the mess.

📝 Editor’s Note:

You don’t get to drop the atomic bomb, change the course of human warfare, and then turn around and act like war is too dangerous to win. Truman went from fire-and-brimstone commander to cautious schoolmarm in record time. The question isn’t why he changed — the question is, how many lives did that change cost?

📚 References:

- Hastings, M. (1987). The Korean War. Simon & Schuster.

- Ambrose, S. E. (1997). Rise to Globalism: American Foreign Policy Since 1938. Penguin Books.

- McCullough, D. (1992). Truman. Simon & Schuster.