In 1993, President Bill Clinton embarked on one of the most ambitious domestic policy initiatives of his presidency: a sweeping plan to reform the American healthcare system. Touted as a fix for the rising costs, uneven access, and complex insurance rules plaguing millions of Americans, Clinton’s proposal ultimately failed—but its legacy still echoes in today’s policy debates.

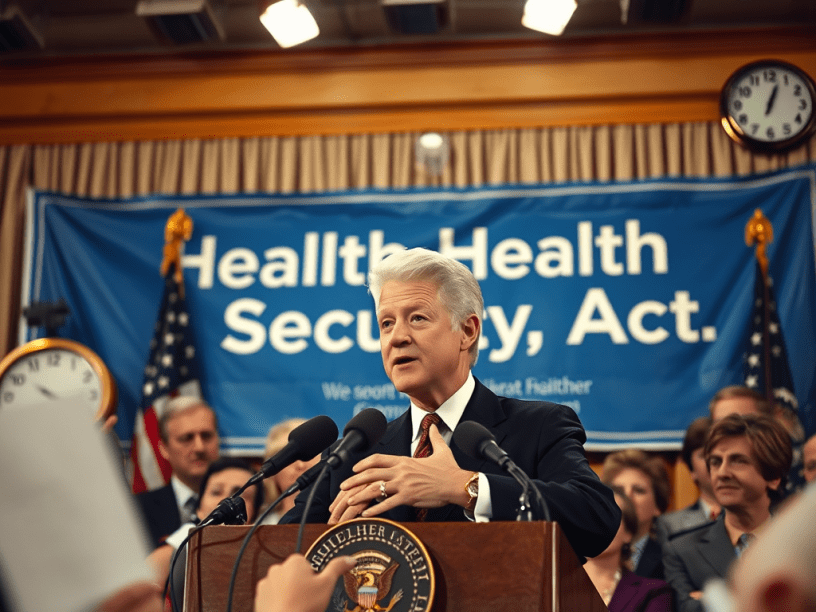

The plan was officially known as the Health Security Act, but it quickly became better known as “Hillarycare” due to First Lady Hillary Clinton’s highly publicized role as the chair of the Task Force on National Health Care Reform. Clinton envisioned a system in which every American would receive a health insurance card, much like a Social Security number, guaranteeing comprehensive coverage regardless of preexisting conditions or employment status1.

At its core, the plan aimed to achieve universal coverage through a system of regional health alliances. These alliances would offer a selection of private insurance plans, all required to meet standardized benefits, and employers would be mandated to provide insurance to their employees or pay into the system. Individuals not covered through work could buy into the alliance plans at subsidized rates.

The administration built a complex policy structure, and that complexity quickly became one of the plan’s biggest liabilities. The sheer size of the proposal—more than 1,300 pages—invited confusion, misinterpretation, and suspicion2. Critics in Congress, including some Democrats, balked at the top-down approach. Insurance companies and small business lobbies mobilized rapidly against the employer mandate, warning of job losses and rising costs.

Perhaps most damaging was the public relations battle. The infamous “Harry and Louise” ads, funded by the Health Insurance Association of America, portrayed a middle-class couple bewildered and endangered by the new regulations. These spots aired widely, framing the proposal as government overreach and stoking fear among voters3.

By September 1994, Senate Majority Leader George Mitchell declared the reform effort dead. Clinton’s failure to pass healthcare reform was a critical blow to his administration and contributed to the Republican sweep of Congress in the 1994 midterms. It marked a turning point in Clinton’s presidency, after which he shifted sharply toward centrist policies.

In hindsight, the 1993 healthcare reform effort was a classic example of overreach without coalition-building. The Clinton team had control of Congress but underestimated the resistance from entrenched interests and failed to engage the public with a simple, clear message. Despite its failure, the plan laid groundwork for future reforms, particularly the Affordable Care Act of 2010, which drew heavily on the idea of regulated competition among private insurers.

Today, Clinton’s 1993 healthcare plan stands as a cautionary tale about ambition, complexity, and the need to win both hearts and minds before policy can become law.

Footnotes

- “Health Security Act of 1993,” U.S. Congress, https://www.congress.gov/bill/103rd-congress/house-bill/3600 ↩

- Hacker, Jacob S. The Road to Nowhere: The Genesis of President Clinton’s Plan for Health Security. Princeton University Press, 1997. ↩

- Blendon, Robert J., et al. “Understanding the Managed Care Backlash.” Health Affairs, vol. 17, no. 4, 1998, pp. 80–94. ↩