📅 August 13, 2025

Clinton: Cut the Capital Gains Tax, Feeding Inequality 📉💼

#Triangulation

Bill Clinton did something in 1997 that, at the time, he sold as both savvy economics and slick politics: he cut the capital gains tax from 28% to 20%. Republicans loved it. Democrats shrugged and went along. Wall Street popped champagne. But Main Street? It quietly braced for the long-term consequences—and they came.

Clinton didn’t just trim a tax rate. He sent a message: investment income should be taxed less than work. That single move fed a growing wealth gap, cemented a preferential system for the already wealthy, and signaled a Democratic embrace of supply-side thinking that would echo for decades.

Out-Reaganing Reagan

The capital gains tax cut wasn’t just policy—it was a political maneuver. By 1997, Clinton had already pivoted hard into “Third Way” centrism, and this tax cut was another jewel in his triangulation crown. His goal? Outmaneuver Republicans on economics by stealing their best talking points. Make no mistake: this was Clinton trying to out-Reagan Reagan.

Supply-side economics—the theory that lower taxes on the wealthy spur investment, growth, and eventually benefit everyone—was core to Reagan’s policy worldview. By adopting the capital gains cut, Clinton adopted the theory, too, but with a Democrat’s smile and a saxophone riff. He made it look bipartisan, technocratic, even inevitable.

But beneath that veneer was a dangerous gamble.

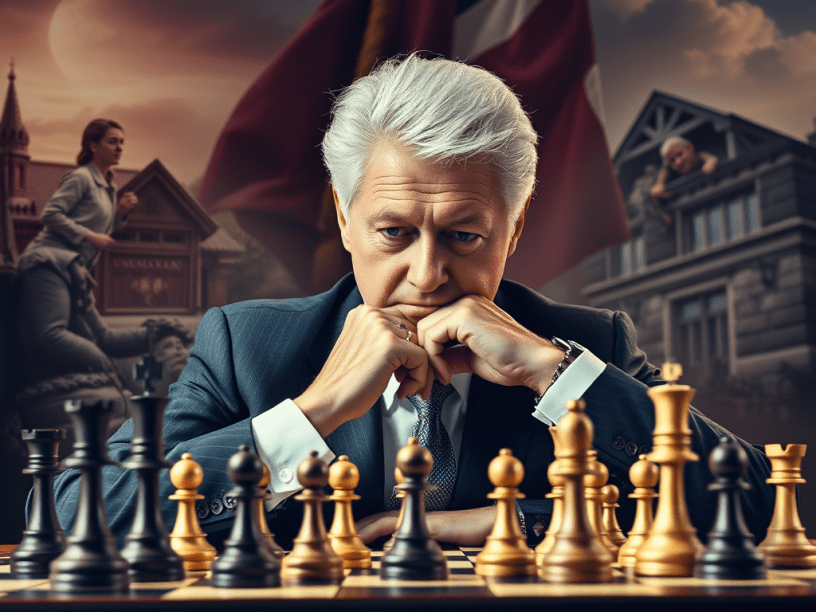

A Gambler, Not a Visionary

Clinton didn’t do this because he lacked morals or intelligence. On the contrary—he was a brilliant political tactician with a magnetic intellect. But he also had a deep faith in his ability to finesse any fallout, any complication. If Reagan had an ideological compass, Clinton had a chessboard. He believed that cleverness could substitute for vision.

This wasn’t a character flaw so much as a governing pattern. Clinton treated policy decisions like collegiate debate tournaments: win the round, score the points, move on. He rarely paused to consider how the seeds he planted might sprout years or decades later—especially in a world he could no longer control.

And the seeds of the 1997 tax cut grew thorns.

The Real-World Fallout

The capital gains tax cut overwhelmingly benefited the top 1% of earners. According to data from the Congressional Budget Office, by the early 2000s, more than 75% of all capital gains income was claimed by the wealthiest households.1 Clinton’s cut supercharged this process. It turbocharged asset price inflation—especially stocks and real estate—and helped widen the gap between those who own assets and those who live paycheck to paycheck.

Research from the Tax Policy Center shows that reductions in capital gains taxes have almost no effect on overall economic growth but significantly increase after-tax income inequality.2 The promised “trickle down” never materialized; what we got instead was a geyser of wealth accumulation for the already-rich.

And worse, this tax policy constrained future Democratic efforts. By embracing capital gains cuts, Clinton shifted the Overton window. Democrats became reluctant to propose tax increases on wealth, fearing accusations of backtracking on “pro-growth” policies. It helped lock in a new bipartisan consensus that investment should be taxed lightly, even as wages stagnated and productivity soared.

The Long Shadow of Triangulation

Clinton’s optimism—his belief that he could walk a tightrope between populism and corporate centrism—defined much of his presidency. But optimism without long-term analysis is a risky bet. His capital gains tax cut is now widely seen as a contributor to the inequality crisis that exploded into full view during the Great Recession, the Occupy Wall Street movement, and continues into today’s housing and financial crises.3

Even Clinton’s own former Treasury Secretary, Lawrence Summers, later admitted that the economic team “underestimated” the long-term impact of inequality and financial deregulation during the 1990s.4

And as economists like Thomas Piketty have demonstrated, when the return on capital consistently exceeds the growth of wages and labor income—as it has since the late 1990s—wealth becomes entrenched across generations, and social mobility collapses.5

Clinton didn’t create inequality. But he greased the wheels of its modern form. He believed he could control the consequences. He couldn’t.

Final Thoughts

Looking back, Clinton’s 1997 capital gains tax cut was not just a tax tweak. It was a philosophical statement: the best way to grow the economy was to favor capital over labor. It was a bet that flattering markets would help the little guy. It was a high-stakes move rooted in faith in his own finesse rather than in any serious long-term economic forecasting.

This wasn’t a man blind to consequences—it was a man who thought he could outmaneuver them. For all his brilliance and charm, Bill Clinton’s presidency often confused tactical genius with strategic wisdom. The rest of us are still living in the fallout.

#Triangulation continues tomorrow.

Footnotes

- Congressional Budget Office. (2000). Effective Federal Tax Rates: 1979–1997. https://www.cbo.gov/publication/12367 ↩

- Tax Policy Center. (2013). Capital Gains Tax Rates and Revenues. https://www.taxpolicycenter.org ↩

- Hacker, J. S., & Pierson, P. (2010). Winner-Take-All Politics: How Washington Made the Rich Richer—and Turned Its Back on the Middle Class. Simon & Schuster. ↩

- Summers, L. H. (2014). Inequality and America’s Long-Term Growth. Harvard University. ↩

- Piketty, T. (2014). Capital in the Twenty-First Century. Harvard University Press. ↩