By Cliff Potts

Dateline: August 18, 2025

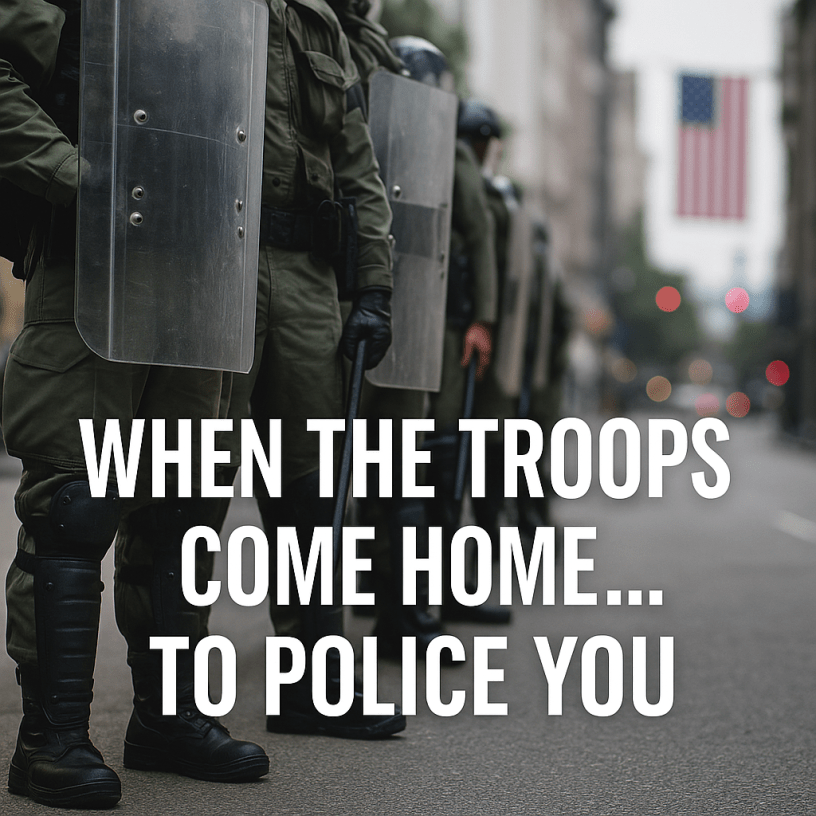

As political tensions rise ahead of the 2026 election cycle, concern is growing that federal military forces could be deployed into democratically governed cities and states under the pretext of restoring order. While the use of federal troops in civilian law enforcement is generally prohibited by the Posse Comitatus Act of 1878, exceptions such as the Insurrection Act have historically been used to justify deployments that skirt the boundaries of legality (Bialik, 2020; Banks, 2020).

Experts warn that such actions, even when clothed in the language of “public safety,” carry profound risks for civil liberties. “The military is trained for combat, not policing,” said a former Pentagon legal adviser. “When they’re tasked with civilian control, the results can be catastrophic” (Banks, 2020).

Legal Lines and Loopholes

Under the Posse Comitatus Act, the Army and Air Force are restricted from domestic law enforcement roles. Similar Department of Defense regulations apply to the Navy and Marine Corps. The Insurrection Act, however, gives the president broad — and controversial — discretion to deploy troops in cases of rebellion, obstruction of the law, or when states request assistance (Elsea, 2018). Critics note that this statute, last significantly updated in 2006, is vulnerable to abuse by an administration seeking political advantage.

State attorneys general and governors retain the right to challenge such deployments in federal court. Legal scholars recommend pre-drafting temporary restraining orders (TROs) and injunctions to be filed immediately should troops be ordered into policing roles without proper statutory authority.

The Historical Record

The dangers of using the military in civilian confrontations are not hypothetical. In 1932, U.S. Army units under General Douglas MacArthur forcibly dispersed the Bonus Army — World War I veterans peacefully protesting for early payment of their service bonuses — with tanks, tear gas, and mounted cavalry (Dickson & Allen, 2004). In 1970, Ohio National Guard troops fired on students at Kent State University during anti-war protests, killing four and wounding nine (Lewis & Hensley, 1998). More recently, in June 2020, federal forces forcibly cleared Lafayette Square in Washington, D.C., ahead of a presidential photo opportunity, raising alarms over the politicization of crowd control (Baker et al., 2020).

Each incident has since been cited as a cautionary tale — a reminder that the misuse of military force against civilians can leave lasting scars on democratic institutions.

Preparing Without Escalating

Civil rights organizations stress the importance of preparedness that avoids crossing into confrontation. The National Lawyers Guild advises demonstrators to carry identification, essential medications, water, and printed “Know Your Rights” information, including hotlines for legal assistance (National Lawyers Guild, n.d.). Nonviolent discipline — avoiding property destruction, physical aggression, or baiting officers — is essential for maintaining public legitimacy and legal standing.

Trained legal observers and independent journalists can serve as critical watchdogs, documenting potential overreach and preserving evidence for later review. Organizers are urged to establish clear exit routes, designate off-site meet-up points, and assign safety marshals to monitor crowd conditions.

Digital security is equally important: location tracking should be minimized, video should be backed up to secure cloud storage as soon as possible, and devices should be password-protected.

A Parallel Track: Courts and Councils

Physical demonstrations are only one part of an effective response. Parallel efforts — legal filings, public hearings, and media engagement — ensure that incidents of federal overreach are challenged in real time. Framing these events as violations of statutory limits and the social contract, rather than “clashes” or “unrest,” keeps the focus on accountability.

A Choice for the Republic

Whether or not federal troops are ever deployed into cities without consent, the precedent such an act would set is deeply troubling. Democratic governance depends on civilian control of law enforcement, and history suggests that blurring that line comes at a high cost. Citizens, advocates, and elected officials have an opportunity — and a responsibility — to prepare now, in ways that safeguard both safety and liberty.

References

Baker, P., Haberman, M., & Shear, M. D. (2020, June 2). How Trump’s idea for a photo op led to chaos in Lafayette Square. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com

Banks, W. C. (2020). Soldiers on the home front: The domestic role of the American military. Harvard University Press.

Bialik, C. (2020, June 3). Why Trump can’t just send active-duty troops into states. FiveThirtyEight. https://fivethirtyeight.com

Dickson, P., & Allen, T. B. (2004). The Bonus Army: An American epic. Walker & Company.

Elsea, J. K. (2018). The Posse Comitatus Act and related matters: The use of the military to execute civilian law. Congressional Research Service.

Lewis, J. H., & Hensley, T. R. (1998). The May 4 shootings at Kent State University: The search for historical accuracy. Ohio Council for the Social Studies Review, 34(1), 9–21.

National Lawyers Guild. (n.d.). Know Your Rights: Demonstrations and protests. Retrieved from https://www.nlg.org