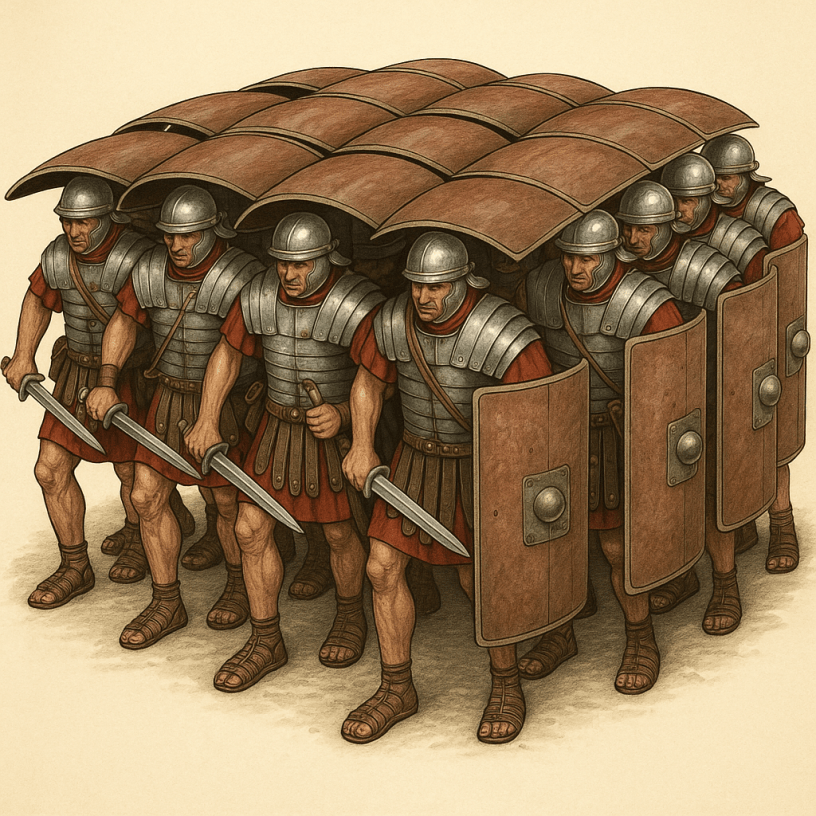

Picture this: you’re a soldier in the Roman legions, somewhere between the 1st century BCE and the 3rd century CE. You’re standing shoulder-to-shoulder with dozens of fellow soldiers, each holding a large, curved rectangular shield (scutum). Ahead is a fortress wall or a hail of arrows. Instead of charging wildly, you and your cohort snap into formation. The front row locks shields in front. The rows behind raise their shields overhead, edges overlapping so tightly that from above, you look like a giant armored box inching forward.

This was the testudo — Latin for “tortoise” — and it was one of the most visually striking and effective defensive maneuvers in military history.

Why It Worked

- Full coverage. The shields created a near-continuous barrier against arrows, javelins, and even stones dropped from above.

- Psychological effect. To the enemy, it looked like an unstoppable armored creature crawling toward the gates. The intimidation factor was real.

- Coordination & discipline. The testudo only worked because Roman soldiers trained relentlessly. One weak link could expose the entire unit.

- Adaptability. It could be used in sieges, open battle, or urban fighting. The formation could move forward, pivot, or even collapse inward to protect from all sides.

Historians like Goldsworthy (2003) note that the testudo was rarely the sole tactic used — it was part of a whole arsenal of Roman battlefield maneuvers — but its symbolic and practical power made it famous.

Why It Lasted Centuries

The testudo’s longevity wasn’t about the shields — it was about the system.

Rome invested in standardized equipment, drilled formations endlessly, and instilled discipline so deep that even under a rain of missiles, soldiers didn’t break formation. That kind of coordination gave Rome an edge in siege warfare and street fighting in rebellious cities.

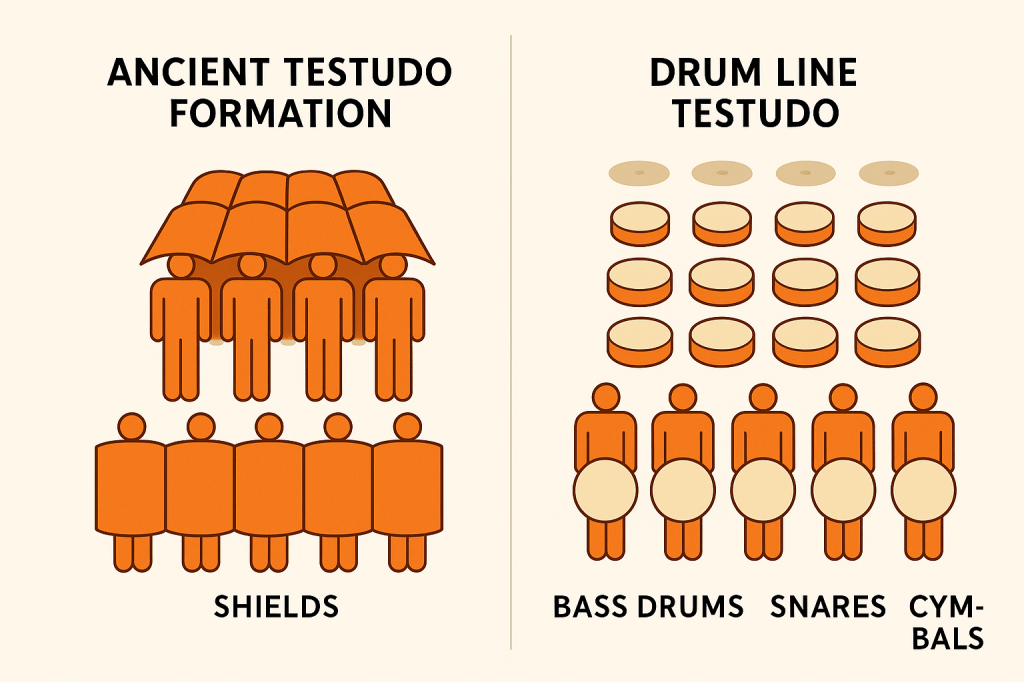

From Siege to Stage: A Modern, Legal Adaptation

Now, let’s fast-forward 1,800 years and swap the fortress for a festival.

Instead of soldiers, picture a drum line at a music event — bass drums up front, snares overhead, cymbals to the sides. They move in tight formation through a crowd, not to break a siege, but to create a visual and auditory spectacle.

- The “shields” are instruments. Big bass drums or large, decorated panels face forward, while overhead percussion gear creates a roof-like visual.

- It’s about unity. Just like the Romans, the key is coordination — everyone moving in sync, creating a living, moving sculpture.

- Crowd engagement. The crowd sees the “tortoise” moving toward them and parts naturally, not out of fear, but curiosity. The music becomes the “psychological effect” — not intimidation, but joy.

- No confrontation, pure performance. This keeps the concept entirely lawful and artistic — you’re borrowing the visual cohesion of the testudo, not its battlefield purpose.

In this way, a piece of ancient military choreography becomes a peaceful, creative crowd-control method at a festival — guiding foot traffic, setting a performance zone, or leading a parade through dense spaces without pushing or shoving.

Sources:

Goldsworthy, A. (2003). The Complete Roman Army. Thames & Hudson.

Connolly, P. (1998). Greece and Rome at War. Greenhill Books.