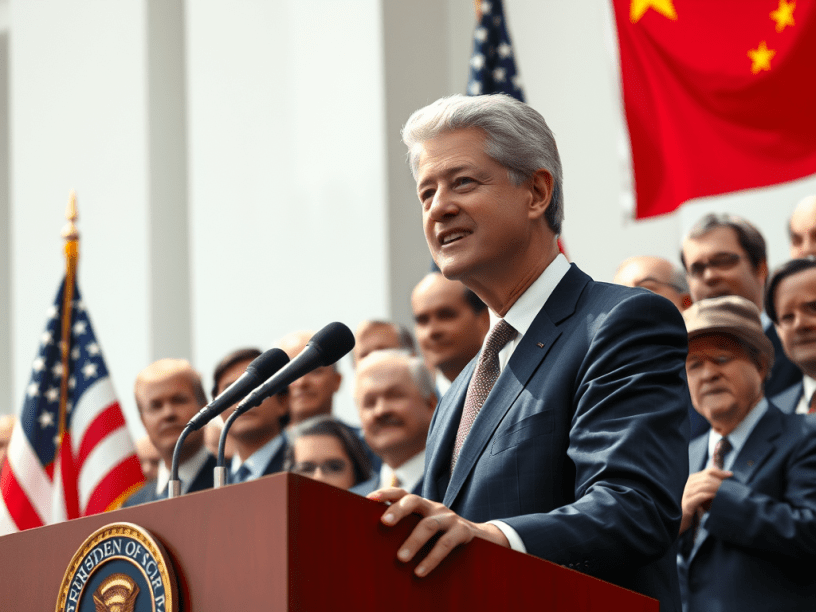

Clinton’s Strategic Bet on China

In the 1990s, President Bill Clinton renewed China’s most-favored-nation (MFN) trade status year after year—despite Beijing’s well-documented human rights abuses.

Initially, Clinton tied trade benefits to human rights “benchmarks.” But by 1994, his administration quietly abandoned those conditions. Human Rights Watch blasted the shift as the end of effective international pressure on China, noting that business interests had clearly won out1.

By removing human rights as a prerequisite for MFN status, Clinton laid the groundwork for a bigger gamble: permanent trade normalization.

Why Clinton Pushed for PNTR

In 2000, Clinton pursued Permanent Normal Trade Relations (PNTR)—a move that cleared China’s entry into the World Trade Organization (WTO).

Clinton pitched it as a “one-way street” for U.S. interests: China would cut tariffs on U.S. goods, while American companies gained access to 1.2 billion new consumers. “Our companies can sell without moving factories there,” he promised2.

But beneath the economic optimism lay political motives. Clinton was reshaping the Democratic Party’s identity around global markets. Centrist Democrats framed PNTR as a legacy-defining victory for “New Democrat” centrism, in the mold of NAFTA.

Clinton also claimed that bringing China into the global trade system would encourage peace and democracy. In his words, this deal wasn’t just about trade—it was about “shaping the future of the 21st century”3.

Divided Democrats, Cozy Corporations

Support for PNTR among Democrats was split. Progressives like Nancy Pelosi and Tom Harkin opposed it, citing China’s brutal crackdowns on dissent, religious expression, and labor. But centrist figures like Joe Lieberman, John Kerry, and Robert Matsui aligned with Clinton, arguing that free trade would empower Chinese reformers.

Dozens of Democrats only came aboard after Clinton offered local sweeteners—worker retraining, export incentives, and district tours.

Corporate America, meanwhile, lobbied hard. Silicon Valley and Wall Street saw enormous potential in China’s markets. Their influence helped neutralize human rights concerns in Congress.

What It Cost the U.S.

PNTR and WTO membership opened China’s floodgates.

Yes, U.S. exports to China surged. But Chinese imports surged more—leading to an enormous trade deficit. A 2016 MIT study linked PNTR to the loss of 2.4 million American jobs between 1999 and 20114.

Worse, China used the deal to demand tech-sharing as a condition for market access. U.S. firms, eager to break in, transferred sensitive technologies to joint ventures—only to see Chinese state-backed competitors rise using that same IP.

The U.S. Trade Representative later confirmed China’s use of “forced technology transfer” and unfair trade practices, especially in AI, telecoms, and semiconductors5.

A Strategic Miscalculation

Far from becoming a peaceful partner, China used its newfound wealth and access to consolidate authoritarian rule.

Beijing cracked down harder on dissidents, built a vast surveillance state, and launched an ethnic genocide in Xinjiang—all while expanding its global influence via trade and infrastructure deals.

In 2021, the U.S. National Security Commission on Artificial Intelligence warned that China’s advances in critical tech—enabled in part by early U.S. concessions—threatened America’s global edge6.

Even today, China retains its PNTR status, while engaging in widespread human rights violations that would disqualify nearly any other nation from such favorable treatment.

Other Nations, Worse Records?

Only a few states with similar human rights abuses—North Korea, Iran, Syria—lack PNTR or WTO privileges. Vietnam, like China, has an authoritarian one-party system but gained PNTR in 2006 after a similar WTO negotiation.

In this context, Clinton’s China decision wasn’t unique—but it was consequential. Because China wasn’t just a big country. It was a rising superpower.

The Legacy of #Triangulation

Bill Clinton’s administration sold China trade as a win-win: prosperity for Americans, progress for China.

But the outcome was more one-sided. Jobs vanished. Technology flowed outward. And a more powerful, less free China emerged.

In hindsight, Clinton’s “Third Way” trade diplomacy looks less like strategy and more like surrender.

Footnotes

- Human Rights Watch. (1996). Business as Usual: The Clinton Administration and Human Rights in China. https://www.hrw.org/reports/1996/Uschina.htm ↩

- Clinton, W. J. (2000, March 9). Remarks on China Trade and the WTO. https://clintonwhitehouse5.archives.gov/WH/New/html/20000309.html ↩

- Clinton, W. J. (2000, May 18). Speech at the National Press Club on China PNTR. Retrieved from White House Archives. ↩

- Autor, D. H., Dorn, D., & Hanson, G. H. (2016). The China Shock: Learning from Labor Market Adjustment to Large Changes in Trade. Annual Review of Economics, 8, 205–240. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-economics-080315-015041 ↩

- Office of the U.S. Trade Representative. (2018). Section 301 Report on China’s Acts, Policies, and Practices Related to Technology Transfer, IP, and Innovation. https://ustr.gov/sites/default/files/Section%20301%20FINAL.PDF ↩

- National Security Commission on Artificial Intelligence. (2021). Final Report. https://www.nscai.gov/2021-final-report/ ↩