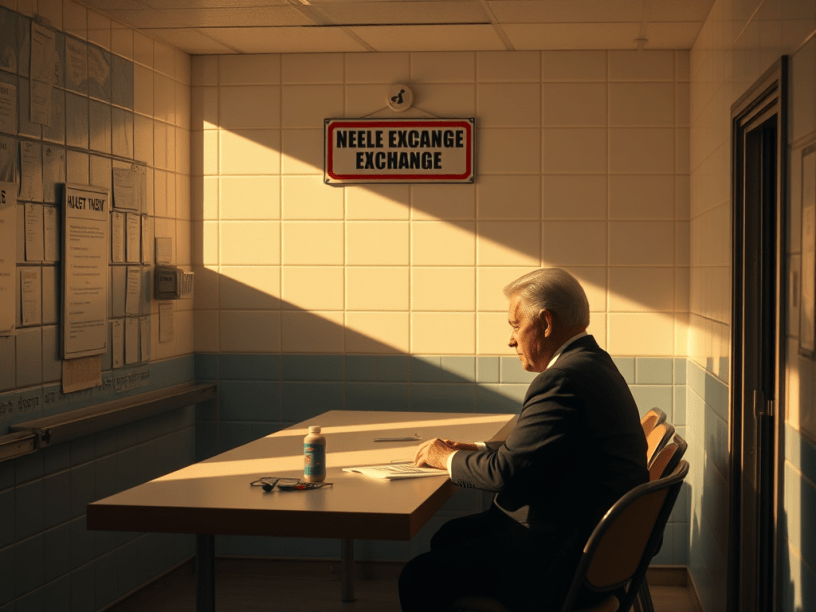

Clinton Blocked Needle Exchange Funding—Evidence Ignored

President Bill Clinton publicly acknowledged that clean needle programs help fight HIV.

But he still blocked federal funding.

The administration stated in 1998 that needle exchanges “help curb the AIDS epidemic,” yet it refused to allow federal money to be spent on them1.

AIDS activists were stunned. Daniel Zingale of the AIDS Action Council said Clinton’s policy was “like acknowledging the world is not flat, then refusing to fund Columbus’ voyage”1.

Despite mounting scientific evidence, Clinton prioritized political caution over proven prevention.

Experts Backed the Science

By the mid-1990s, the scientific community had reached consensus.

A National Research Council panel concluded that needle exchange programs reduce HIV transmission without increasing drug use2.

Surgeon General C. Everett Koop, the CDC, and leading public health researchers all supported lifting the funding ban2.

Even Clinton’s own Secretary of Health and Human Services, Donna Shalala, told Congress that six independent studies, including one from the NIH, proved exchanges did not lead to more drug abuse3.

She called them “another life-saving intervention”3.

But the Clinton administration left the funding ban intact—until 1998, when Congress made it permanent.

Public Health Paid the Price

The cost to public health was severe.

By the late 1990s, one-third of U.S. AIDS cases were tied to injection drug use1.

Yale researchers found that New Haven’s needle exchange program significantly cut new infections. Without it, 64 in 1,000 users would contract HIV. With it, that number dropped to 434.

Researcher Peter Lurie warned that, without federal support, needle programs would never scale to meet demand1.

Some estimates say the federal ban on funding during the worst years of the epidemic likely cost thousands of lives5.

Why Clinton Chose Politics Over Prevention

Clinton’s choice wasn’t about science.

It was about politics.

After Democrats lost Congress in 1994, Clinton embraced a centrist strategy known as triangulation—positioning himself above the left-right divide.

In this case, he embraced the science while blocking funding, keeping conservatives on his side.

Shalala later admitted, “the issue was not the science… it was a policy issue” about whether federal or local governments should act6.

Staffers even described it as “the best of both worlds”—they appeared to support evidence-based policy, while avoiding backlash from Republicans6.

This was classic triangulation: signal support for good policy, but don’t actually enact it.

The Moral Argument Replaced the Scientific One

By 1998, Clinton officials quietly endorsed needle exchange science.

But Congress had already acted.

Clinton signed a budget law continuing the funding ban, making sure federal dollars would not go to syringe programs.

Senator John Ashcroft cheered the move, saying exchanges sent an “intolerable message” that drug use was acceptable3.

Even Democrats feared looking soft on drugs.

Dr. Michael Merson, then Dean at Yale’s public health school, said public health policy was being judged morally, not medically7.

Researcher Robert Heimer added that when science was no longer in dispute, critics fell back on ideology and fear7.

Regret—Too Late

By 2002, Clinton admitted he should have lifted the ban sooner.

But by then, the damage was done.

Millions at risk never got access to a proven harm-reduction tool. Thousands may have been infected who didn’t have to be.

For many public health experts, this episode captures the cost of triangulation—political cover bought with real human lives.

When politics wins and science loses, the sick and vulnerable pay the price.

Footnotes

- Goldstein, A. (1998, April 21). U.S. won’t fund needle-exchange programs; Clinton administration’s position shocks AIDS activists. The Washington Post. ↩ ↩2 ↩3 ↩4

- Curtis, C. (2001). Needle Exchange and AIDS Prevention: Scientific Research Supports Public Policy. American Journal of Public Health, 91(5), 693–695. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.91.5.693 ↩ ↩2

- Padamsee, T. J. (2018). Culture in Action: Interpreting the U.S. Response to HIV/AIDS. Social Science & Medicine, 200, 45–53. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2018.01.001 ↩ ↩2 ↩3

- Heimer, R. (1998). Can syringe exchange serve as a conduit to substance abuse treatment? Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 15(3), 183–191. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0740-5472(97)00213-0 ↩

- Lurie, P., & Reingold, A. (1993). The Public Health Impact of Needle Exchange Programs in the United States and Abroad. University of California, San Francisco. ↩

- Shalala, D. E. (1998). Testimony before Congress on the efficacy and legality of needle exchange programs. HHS Archives. ↩ ↩2

- Merson, M., & Heimer, R. (1999). Needle Exchange in the Context of HIV/AIDS Prevention: Evidence and Ethics. Yale Public Health Review. ↩ ↩2