Chicago, Illinois – November 19, 1899

Detective Silas Marsh didn’t believe in ghosts.

He believed in broken men and fractured motives, in confession slips and bloodstained shoes. But when the witness said the man who escorted Miss Clara Thompson from the Palmer House Grand Ballroom had “ice-blue eyes and a razor mustache,” something in Marsh’s gut shifted.

Herman Webster Mudgett, alias H.H. Holmes, had died on May 7, 1896, hanged and buried in cement. Silas had cut out the newspaper article and filed it beside his collection of oddities—men who drank quicksilver, women who claimed to speak to angels. Holmes, of all men, had deserved Hell.

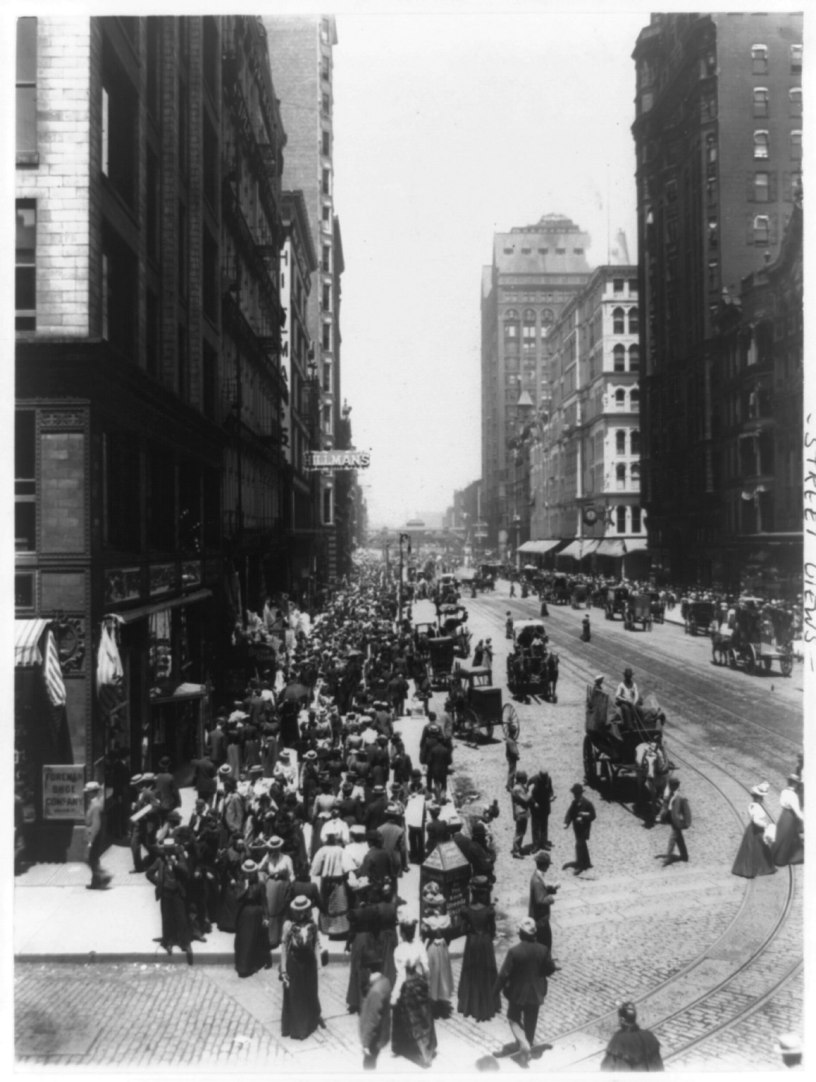

But now, in late 1899, with a chill wind curling through the soot-stained alleys of the Loop, Silas found himself following footprints toward Englewood again.

The ruins of the Murder Castle squatted like a burned-out tooth. Only a few blackened beams remained, and a crumbling section of stone basement. Marsh stepped inside by lamplight. He didn’t expect to find Clara, or answers—just the chance to shake loose the unease burrowed in his bones.

Instead, he found a light on.

A single gas lamp flickered in what should have been cold, empty dark. Beneath it, on a table half-sunk into dirt, was a worn recruitment ledger for “The Holmes Trust.” Names filled it in thick iron ink—names of women who had gone missing during the World’s Fair. At the bottom, a new name had been added.

Clara Thompson. November 18, 1899. Room 313.

Marsh turned slowly. Behind him, the shape of a man stepped forward, tall and shadow-lined.

“I’m afraid I’m no longer accepting visitors,” the man said smoothly. His voice was familiar in a way that made Silas’s stomach tighten.

“Holmes?” Marsh asked, before he could stop himself.

The man smiled—cold, amused. “Names come and go, Detective.”

Silas raised his lantern, but the man was gone.

And the ledger—gone too.

Only Clara’s photograph, scorched at the edges, lay in the dust. Scrawled on the back:

“She signed. That’s all that matters.”

Marsh filed his report. Officially, Clara had fled the city. Unofficially, he stopped sleeping well.

Years later, a letter arrived at his desk. Postmarked Paris, 1906. Inside was a photo of a woman who looked like Clara—slightly older, dressed in black, eyes empty as a doll’s. She was standing beside a man in a bowler hat with a mustache and ice-pick eyes.

On the back: “Room 313.”