December 26

“For those who dare to dream with dirt under their nails.”

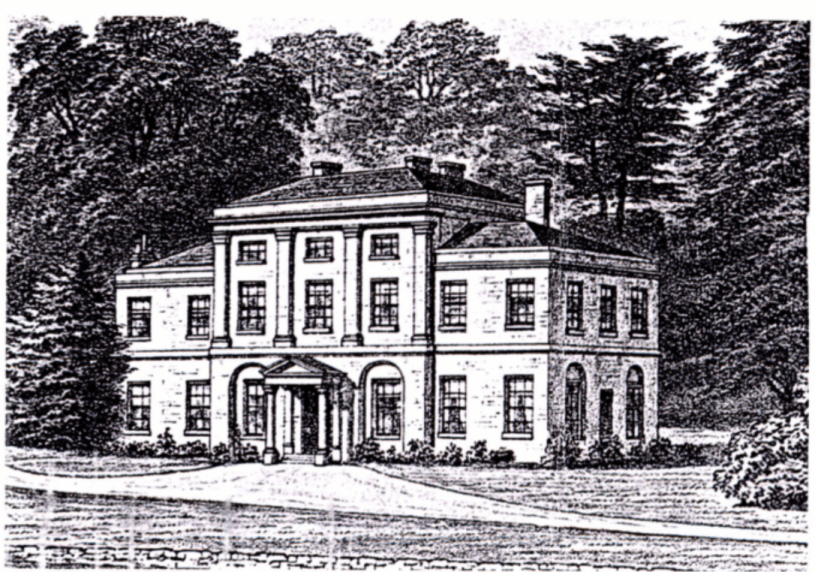

They arrived the day after Christmas, the family of four, weary from a season of cheer that never quite reached their doorstep. The manor was cheap—too cheap—and stood on a snow-covered hill like a secret no one wanted to remember.

Frostwood had once belonged to a quiet novelist. Never published. Never praised. She’d lived there with her typewriter and her ghosts—real or imagined—and left behind rooms full of stories no one ever read. She’d died at her desk. The papers were scattered like fallen leaves when the realtor first opened the door.

The new owners, a working-class family who’d scraped every penny to make this dream happen, moved in with plastic tubs full of discount ornaments and secondhand furniture. The children loved the fireplace. The mother liked the silence. The father muttered, “Let’s give this a year.”

But the manor had opinions.

It began in the nursery. Laughter that didn’t belong to the children. Cold drafts that hissed full sentences when no one was listening. Then the typewriter began to click in the night.

The mother found it first: the final manuscript. Titled “For Those Who Dared to Write Without Permission.” And underneath, a note written in cramped hand:

“They laughed at my prose because it was plain. They said I lacked the polish of their degrees, the pedigree of their literary salons. But I wrote because the stories came, and that should have been enough.”

Later that week, the mother started writing again—something she hadn’t done since her early twenties, when her composition professor told her she’d “never have the grace of Austen or the guts of Atwood.”

Then the whispers started. Not in menace, but in encouragement.

Write it down.

They can’t kill the story if you tell it.

Let them scoff. The hungry know the truth.

One night, while sitting alone in the attic, the father—who’d built roads, who’d worked graveyards, who’d never thought himself poetic—heard a voice behind him say:

“It’s not the grammar that makes you worthy. It’s the fire in your belly. Let it burn.”

And so he wrote, too.

They all did.

Frostwood Manor hummed with creation. Pages rustled in empty rooms. Pencils rolled off antique desks without being touched. The children whispered bedtime tales to ghosts who listened with interest and never interrupted.

The manor had never wanted silence. It had wanted a legacy.

And the haunting? That was never malevolent. It was a chorus of the dismissed, the overlooked, the writers without workshops or agents, the ones who wrote during lunch breaks or between shifts. They haunted Frostwood not to scare—but to say:

We mattered. You do, too.